Owen Sound's Black History

Owen Sound’s Black History

The history of Owen Sound is incomplete without mention of its Black settlers, who were part of the community at its inception. Owen Sound was the last terminal of the Underground Railroad, the route slaves fleeing from the Southern states took to Canada.

It was an attractive destination for two reasons. First, fewer bounty hunters travelled this far north in search of escaped slaves. There are records, however, of unpleasant confrontations between bounty hunters and local residents in the ports on the lake and the bay. The second reason is that the area was newly opened for settlement, so former slaves had an opportunity to own property and settle in their new home. Unfortunately, white settlers bumped many families who had settled on area farmland. Some of these families then moved to Owen Sound.

In 1843, Owen Sound’s first and most famous Black resident, John “Daddy” Hall, arrived on the side-wheel steamer, Ploughboy. The Village of Sydenham, as Owen Sound was then known, was only a few years old. Hall and several other Black families resided on the heavily wooded east hill, later known as the Pleasure Grounds and now part of Victoria Park.

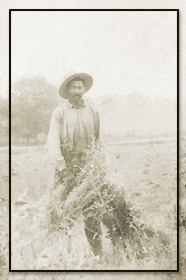

Early Black settlers experienced similar challenges to those of their European counterparts. They cleared huge trees and dense bush to create farmland. Changing weather, wild animals and loneliness were encountered by Black and white alike. An added challenge for the Black settlers, however, was the persistence of racism and discrimination; they were often treated as second-class citizens. Those dwelling in town were often restricted to lower-status, menial jobs.

Escaping from slavery was a long and tough journey, full of danger and fear. Although free, Black settlers and their descendants were outsiders on the basis of skin colour. Strong family ties and a strong spiritual faith helped them to build a sense of community, mostly through the British Methodist Episcopal (BME) Church. Music, too, played an important role in both daily life and that of the BME Church. An all-Black big band, the 16-member “Sea Island Merrymakers”, included banjos, guitars, violins, percussion and mandolins among their instruments. The pursuit of education was given a high priority and children were encouraged to obtain as much education as possible.

Blacks in Owen Sound were employed as porters and bellmen in hotels and on trains, as labourers, sailors, cooks, storekeepers, teamsters, barbers, whitewashers, confectioners, farmhands, butchers, maids, waiters, masons and stonecutters. It was difficult for most Blacks to rise through the ranks because of their colour.

According to the 1872 Census, 672 blacks lived in Owen Sound, making up 10% of the City’s population. Many of these lived on the east side of Water Street North (which is now 2nd Avenue East), between 12th and 13th Streets. Today, only a handful of black families make Owen Sound their home.

John and Mary Frost, one of the Village’s prominent families, offered shelter and assistance to runaway slaves. Their limestone home was located on the west escarpment. John was Mayor for a time, as was his son, John III. The younger John, a lawyer, wrote a book called “Broken Shackles”, based on the stories told to him by a former slave, James Henson (whose slave name was Charley Chase). The book was published under the pseudonym, Glenelg, to protect John’s family from anti-Black sentiment.

The Bluewater Highway (Highway 21 from Sarnia to Southampton) is sometimes thought to be named for the path Blacks travelled on their way to Owen Sound. As an inland route, slaves preferred to travel it because bounty and slave hunters in American patrol boats could not spot them from the water.